Flutes, Old

As it happens, I know a little about prehistory. The downside of trying to shine bits of light into the deep dark of our human past is, short of someone suddenly inventing a working Wayback Machine, it is just really hard to finalize with absolute assuredness what happened, say, 40,000 years ago. Nevertheless, we continue hacking away at bits and pieces and are constantly getting closer. At the very least, we keep refining our questions in ever tighter ways.

Many archaeologists would say that our specific species started developing complex thought and communications between 250,000 and 320,000. (Other’s might argue that we are still a work in progress on the whole thinking thing.) That gives us maybe 50,000ish years of brain prep time after the emergence of anatomically modern humans. Let’s give ourselves a around 100,000-200,000 years to start working up real no-doubt-about-it symbolic thinking. So, by 70,000 years ago we are really just abstract thinking machines…relatively, speaking at least. Drop a few more millennia, multiply by ten, and one day you get a Beethoven asking for more double basses to really fill out the sound. Now, narrow it down so instead of looking at 150,000 years its more like 150, and you have Scott Joplin writing movie soundtracks without even knowing about it. Forward a few more decades and you have music streaming out of your phone.

And all of this is relevant because I had this idea that I would do a sort of semi-informative blog on the origins of music. I have now started doing a little research and realize that there is a lot (unrelated tangent: I had a professor in college, can’t remember her name now – tall, the kind of old school teacher who felt like the available textbooks were substandard so she created several of her own but never got around to publishing them…you just walked around with these great, thick photocopied things into which she had hand drawn her illustrations between dense prose – English Grammar 300/400 something, I think – she had very definite feelings about “a lot” being a place one parked cars…”alot” meant many…Microsoft and WordPress, apparently disagree…and, she would have covered this tangent with soooooo much red ink, I bet she is spinning in grave right now…sorry, Dr. Whateveryournamewas…you were a good teacher) to know. Really, there is far more than I could cover easily in a few hundred words.

Okay, I said from the start this was going to be a learning experience. I figured out how to make a Contact webpage. This should be no problem…

Golly…there really is a lot/alot to learn out there…books worth…

(Interesting side note: There seems to have been a shift in the nomenclature in the last few years from “Music Archaeology” to “Sound Archaeology”. I’m guessing, and presumably this will come to light as I read a bit more, that it has something to do with academic researchers not wanting to impose the term “music” with all of its implied definitional subtleties on a larger idea.)

Maybe, we start somewhere in the middle of the story. And, even though I am talking about firsts here for the next little bit, it turns out those firsts are an end point of a long chain of creation and evolution.

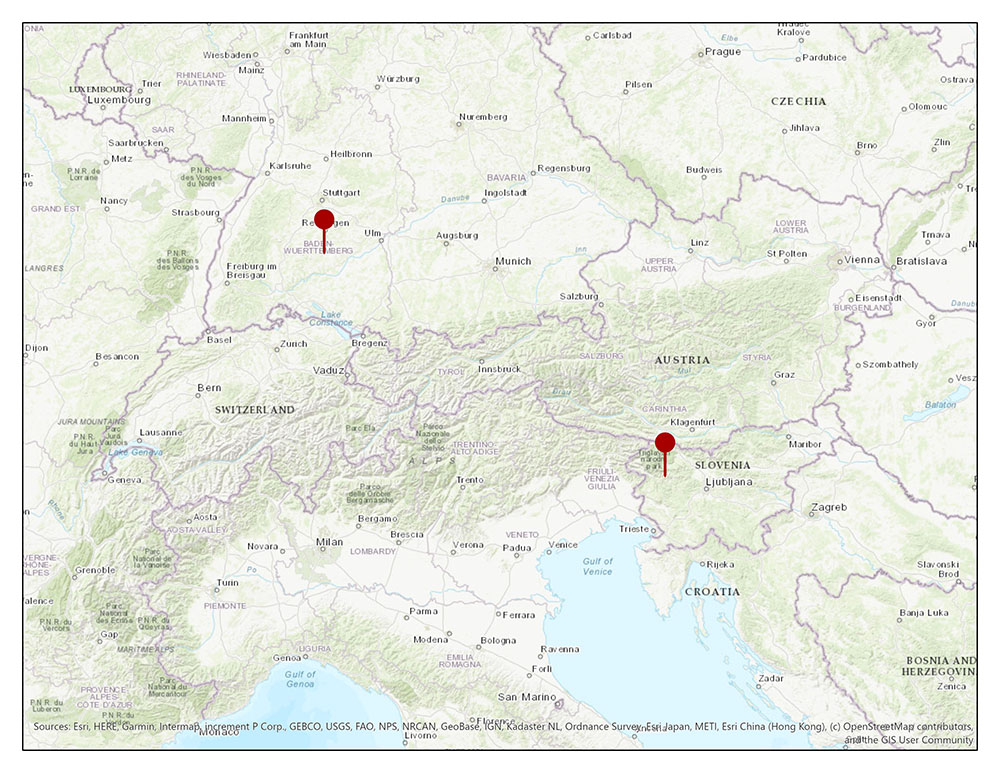

For quite some time, the first instrument was thought to be a flute like artifact made from the femur of a juvenile bear found in Slovenia. Dated to about 43,000 years ago, the popularly labeled Divje Babe Flute made a, relatively speaking, big media splash when it was announced. It is also sometimes referred to as the Neanderthal Flute for the presumed manufactures and players of the flute. A few inches long with a couple of holes along one side of it, the Divje Flute certainly looks like a, well, flute. But, here’s the thing (and in archaeology there is almost always a “here’s the thing”) , after much careful consideration and study, it now seems likely those perfectly placed finger holes were made by animals and not lovingly crafted by sensitive Neandertal craftsmen (which isn’t to say there weren’t sensitive Neandertals…I rather like to think there were…and they may come into play in the next blog about the origins of music). Now, there are still those out there who will fight tooth and nail against the idea that the Divje Flute is anything other than a real and, if not whole, partial instrument. There is occasionally a whiff of conspiracy theory to the defense of the artifact these days. For instance, I have heard defenders of the artifact pointing to the alignment of the “finger holes” and researchers’ apparent willful contrary mindedness in ignoring said alignment. First of all, the kind of person who would spend days and days studying something like this artifact just doesn’t ignore the bloody obvious. Think of it as basic professionalism. Second, nature. I remember bringing a stone I was sure was a well-used tool to a professor to get his input. The stone was broken on two sides creating a truly amazingly perfect right angle. The professor took it in his hand, rolled it over a few times and handed it back saying, “Isn’t nature amazing sometimes.” I took the stone back, went down to my lab, pulled out a microscope, and spent the next hour studying and comparing it with actual artifacts. The sure signs of human agency did indeed turn out to be nothing more than the stone’s natural grain. There was a longer learning process that followed, but the result remained the same: even though it looked like a Native American artifact, it just wasn’t. The lesson: nature can make things so apparently perfect that, I guess because we are so removed from it in the modern world, it’s hard to believe people didn’t have a hand in those things’ creation. This is the case with the Divje Flute.

(Second side note, and surprisingly enough sort of paralleling the first one: The flute in question is often referred to as the “NeanderTHal” flute. The species in question is formally called Homo neanderthalensis. But, in most of my reading over the years, they are labeled “NeanderTals”. Here is a good article about what the differences is and if it makes any big difference. If article skipped, goto short version: current anthropologists dislike the idea of associating the species with ye olde concept of the big, dumb, brutish caveman (EEGAH!). Thick though their brows may have been, their brains were probably bigger than ours, and thus, not necessarily complete thickos were they. I will probably stick with what the way I have been writing it for years. So, as you dive into the next paragraph and look back over the last and notice the slight difference in spelling, that’s why: habit.)

The first good evidence for music making as we might think of it is from about 35,000-40,000 years ago. At a site called Hohle Fels, in a part of southern Germany with the thoroughly lovely sounding name of the Swabian Jura (and, if you are interested, a seven to eight hour drive to the northwest from the Divje find, depending on time of day and weather conditions), a number of smallish flutes were excavated. Made out of the radius of a griffon vulture, the most complete example measures about 22cm long and has five finger holes and a modified end for a mouthpiece. The flutes were uncovered in the lower levels of the site associated with the Aurignacian tradition (that’s a 25 cent phrase for the earliest modern human inhabitants of Europe). Also found at the site were a number of figurines carved from such exotic material as mammoth ivory. Now, here’s the thing here: the oldest flutes were dated to about 35 kya. Buuuut (in lilting tones), the lowest Aurignacian layers date back another 5,000 years. After that it looks like there was a Neandertal occupation at the site. The flute and certainly the figurines show a really quite high level of craftsmanship. These were not sort of one-off creations made while sitting bored around the fire one night. What has been found is probably the result of generations of refinement on a technological model, the template or earliest prototypes, if you will, still remaining to be uncovered. And, once more, here’s the downer thing here: it is very unlikely those earlier instruments will ever be found. Being made out of extremely perishable material like bone, conditions have to be just so for the hypothesized artifacts to survive 40,000 years. The two things that allowed the Divje bone to survive were that it was a large, heavy bone and that it had just so conditions in its cave. The humans, apparently, were making their early flutes out of bird bones. That immediately takes away the heavy and large condition that helped the Divje bone to last until now. We are left hoping for more just so conditions.

And, I kind of got off on a bit of a taphonomy jag there (although it is very interesting). There are at least two things that should probably be pointed out about the Hohle Fels flutes. First, the association with things like female figurines strongly point to an already well-developed capacity for abstract and symbolic thinking in our Paleolithic ancestors. This in turn implies that we, as a species, had been working on this kind of thinking for quite some time pre-these-folks settling down for spell to jam out in the picturesque hills and valleys of Southern Germany. Second, the fact that there were multiple flutes found at the site points to the relative importance that music played in those 40,000-year-old ancestors’ lives.

I plan on spending a few words in an upcoming blog looking at why music might have been important to our ancestors and what the evolution of human cognitive abilities that lead up the music making at Hohle Fels might have been like. For now, here is a quick word from the man who put the whole evolution thing on the map as to what he thought might have led up to anatomically modern humans sitting around rocking and rolling come a Saturday night:

“[The struggles of males to find female mates] are generally decided by the law of battle; but in the case of birds, apparently, by the charms of their song, by their beauty or their power of courtship…” – Chuck Darwin from The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872).

Music listened to while writing:

Eberhard Weber – Colours

P.S. A note on last link: I am in no way affiliated with HDtracks.com, nor will I get a percent of sales if you buy the album. It just happens to be where I purchased the it. I will say, though, to my ears, it sounds really quite good. Maybe at some point I will explore associate linking.

Recent Comments